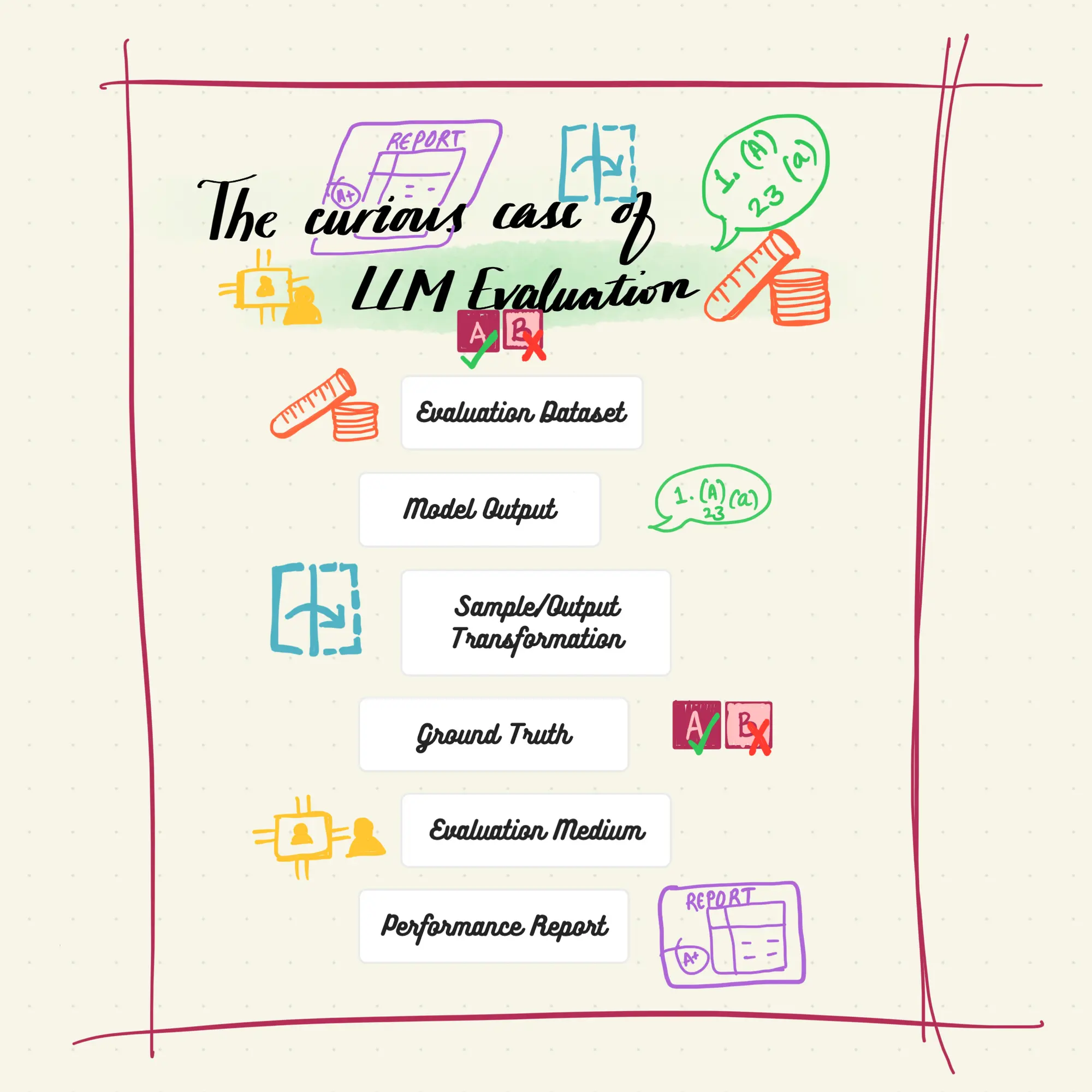

CAPSTONE: Capability Assessment Protocol for Systematic Testing of Natural Language Models Expertise

Introduction

"LLMs", or Language Models, need to be trained and tested on different datasets and prompts to improve functionality and accuracy. In addition, versioning is important when assessing LLMs. Iterating on the prompts and datasets can produce better results. However, keeping different versions of both prompts and datasets can help identify which changes led to improvements in performance. All these practices should be followed to effectively evaluate and improve LLMs.

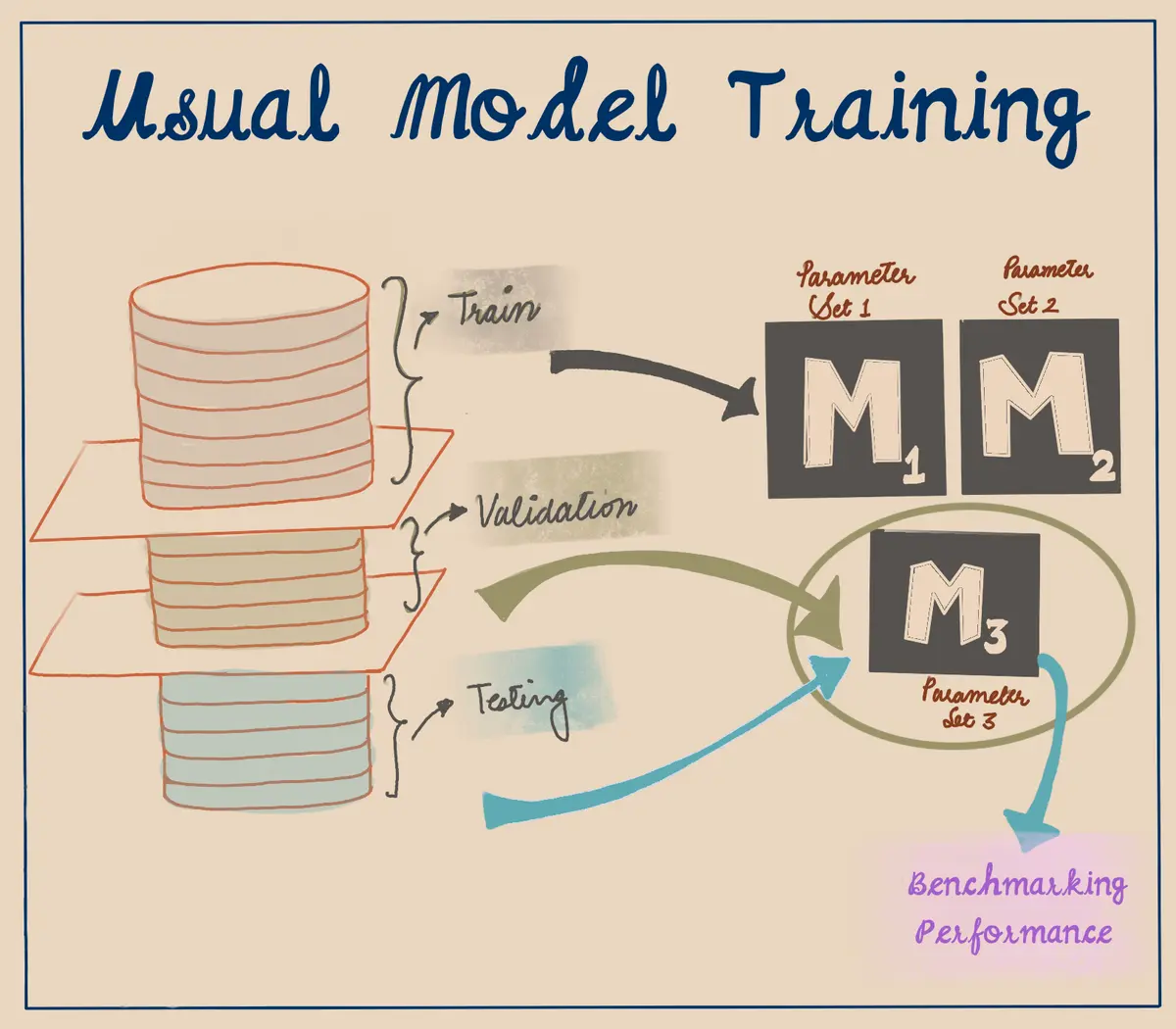

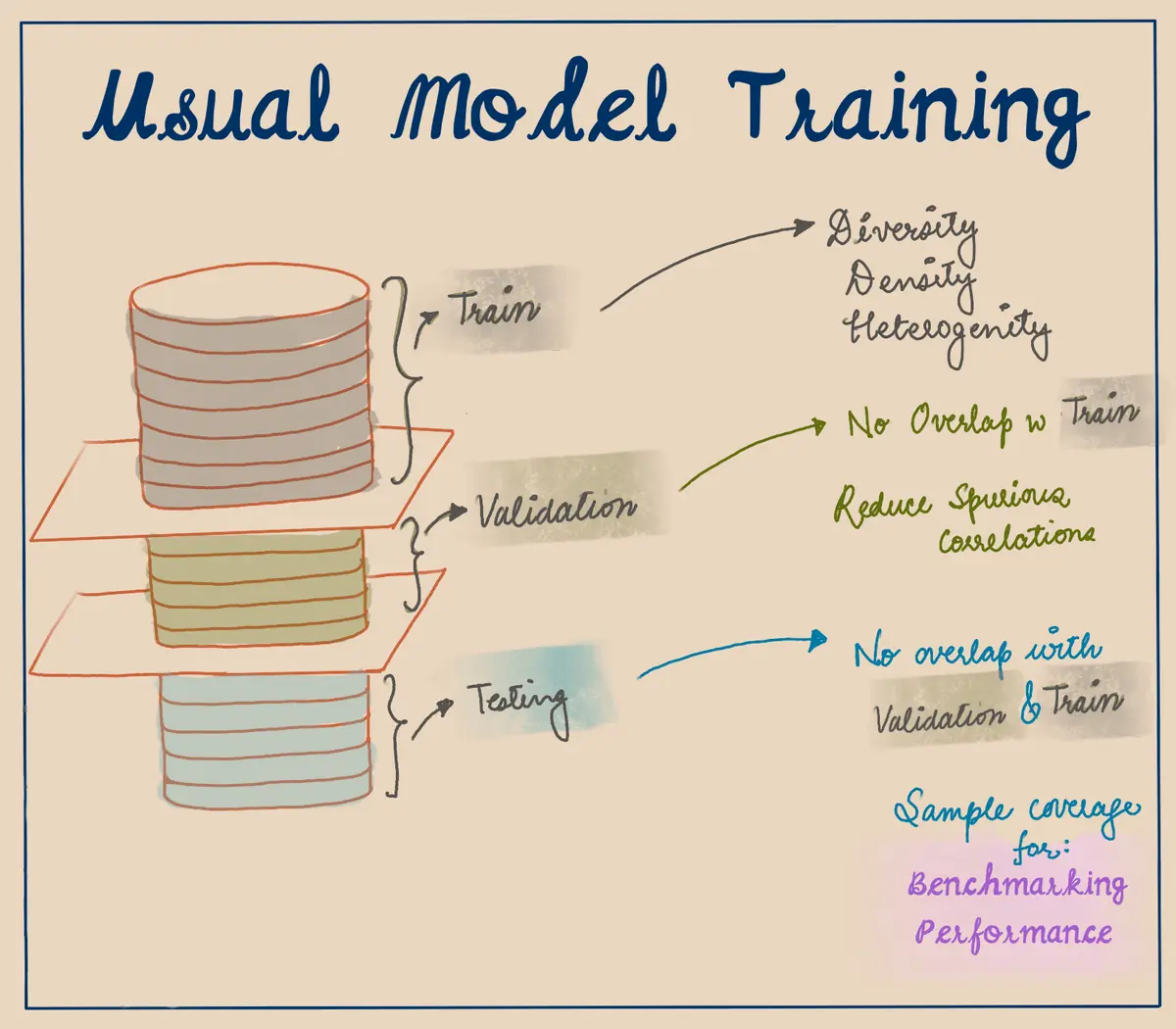

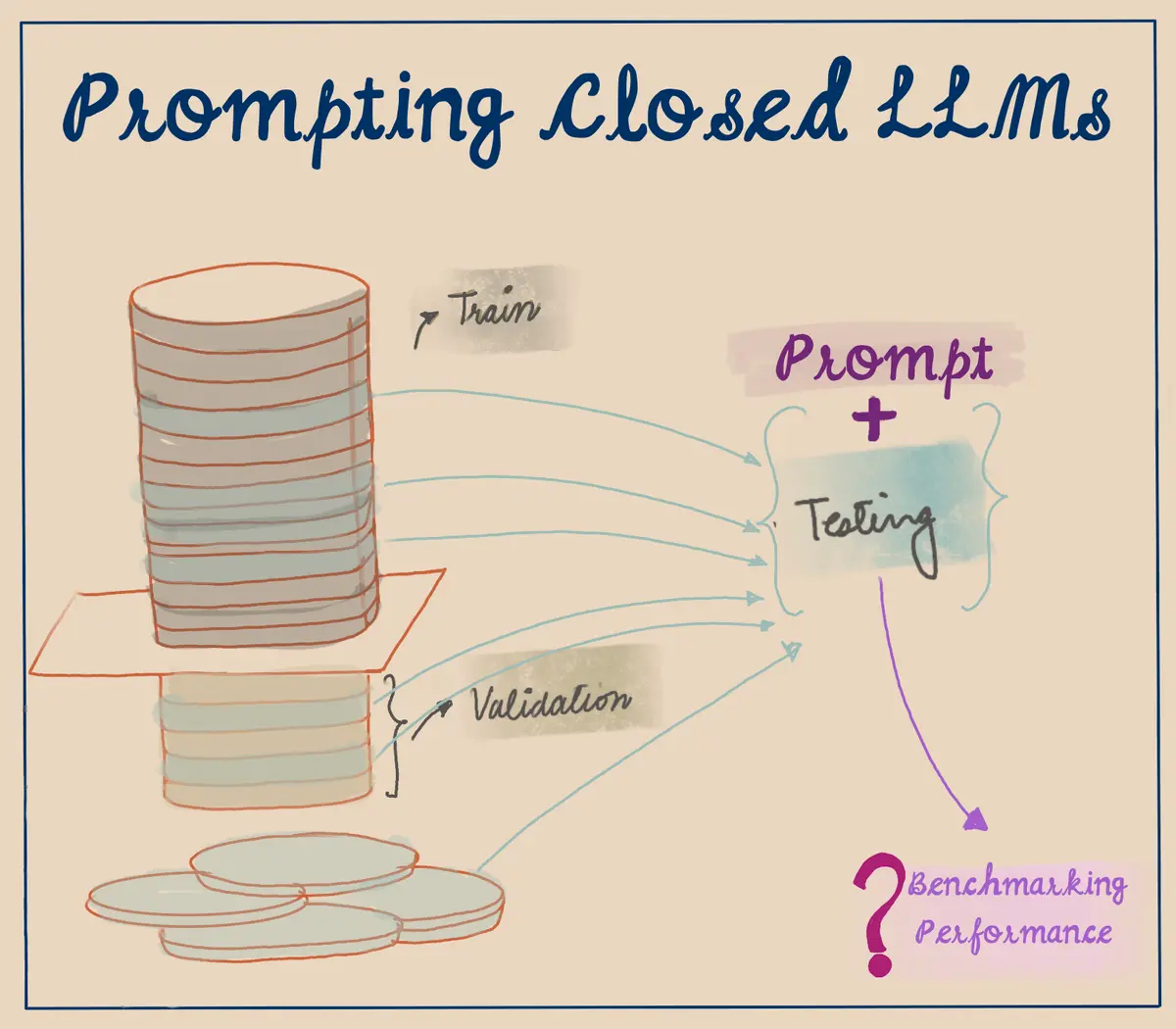

What does usual model training look like?

In machine learning, it's common to divide a dataset into three parts: the train set, validation set, and test set. The train set is used to train a machine learning model, the validation set is used to tune the hyperparameters of the model, and the test set is used to measure the final performance of the model.

There are some pre-established norms when it comes to creating these subsets. For instance, the training set should be diverse and heterogeneous, while the validation and test sets should not have any leakage or spurious correlations from the train set. By following these best practices, data scientists can create effective and accurate machine learning models that can be used for a wide range of applications.

Problems with Closed LLMs

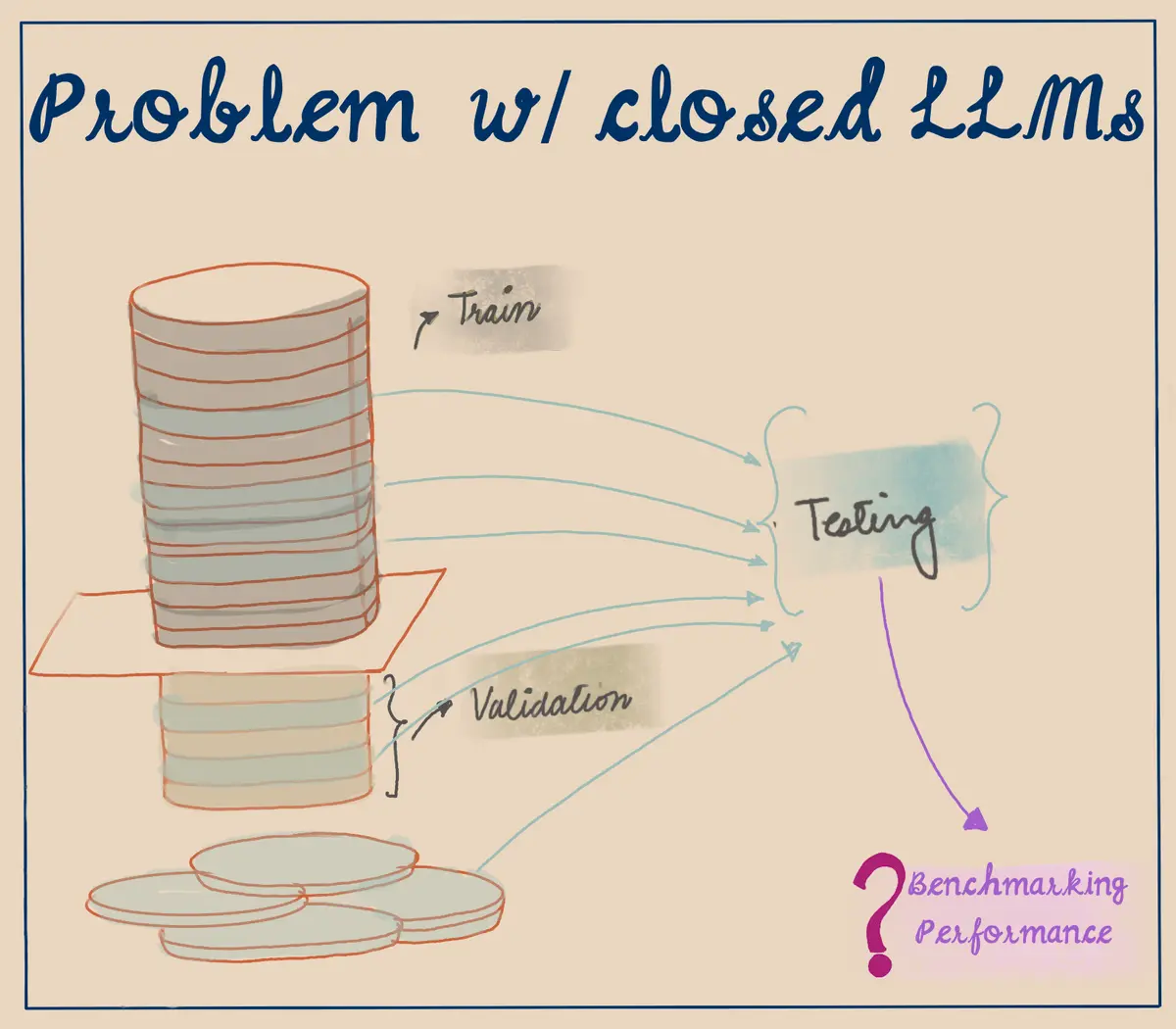

The use of closed language models (LLMs) poses certain challenges when it comes to testing their performance. If we do not know what went into the training dataset of a closed LLM, it is very likely that the test dataset we use or generate will be contaminated. This can result in inaccurate performance metrics and difficulty in verifying the correctness of the model's responses.

Prompt-based benchmarking can exacerbate these challenges further by introducing another layer of complexity. If we are not directly testing for an "input sample" to "output" correspondence, the way we write the prompt and what we ask for as an output will significantly change how we benchmark the ability of any model. This can make evaluating the performance of a closed LLM more difficult and error-prone, and increase the risk of producing biased results.

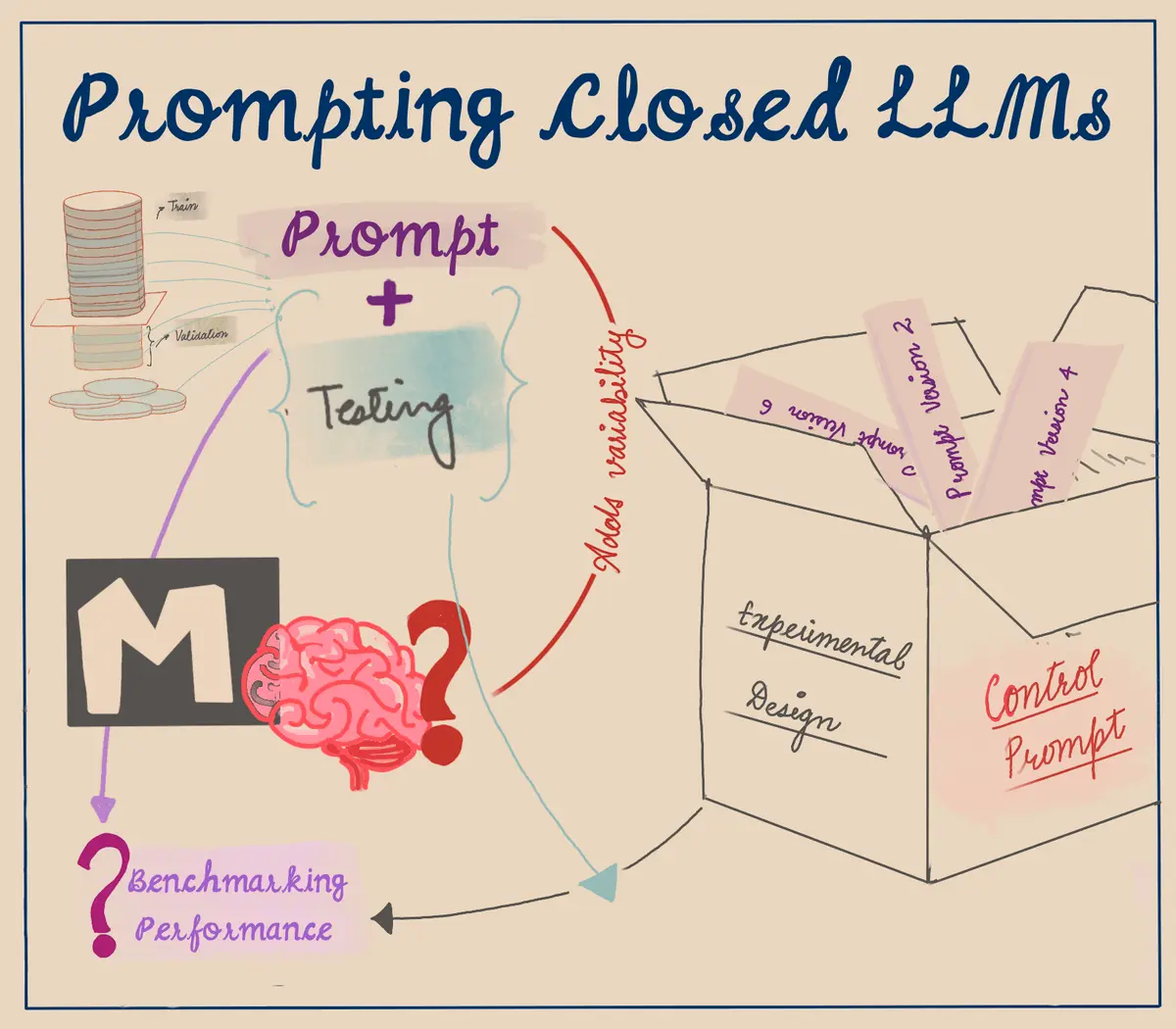

Prompting Closed LLMs

When we are limited to observations, it becomes essential to employ experimental design in order to assess the capabilities of a model.

In order to do effectively, there are three key components we require:

- Firstly, we need to establish controls, which serve as the baseline for comparison and help us understand the impact various factors on the model's performance.

- Additionally, conducting experiments allows us to systematically manipulate variables and observe their effects on the model's outcomes.

- Lastly, carefully considering and accounting for variables is crucial in order to ensure the validity and reliability of our experimental results. By incorporating these elements into our approach, we can effectively evaluate and judge the capabilities of a model limited.

Prompt Based Experimental Design Schemas

Let's talk about Prompt Based Experimental Design Schemas. These schemas can be thought of as templates, but with a key distinction. They not only focus on varying the input sample, but also on modifying the prompt specifications. By doing so, they allow us to closely monitor and analyze the changes that occur from one prompt to another. This approach provides a valuable way to study and understand the impact of different prompts on the overall outcome of an experiment.

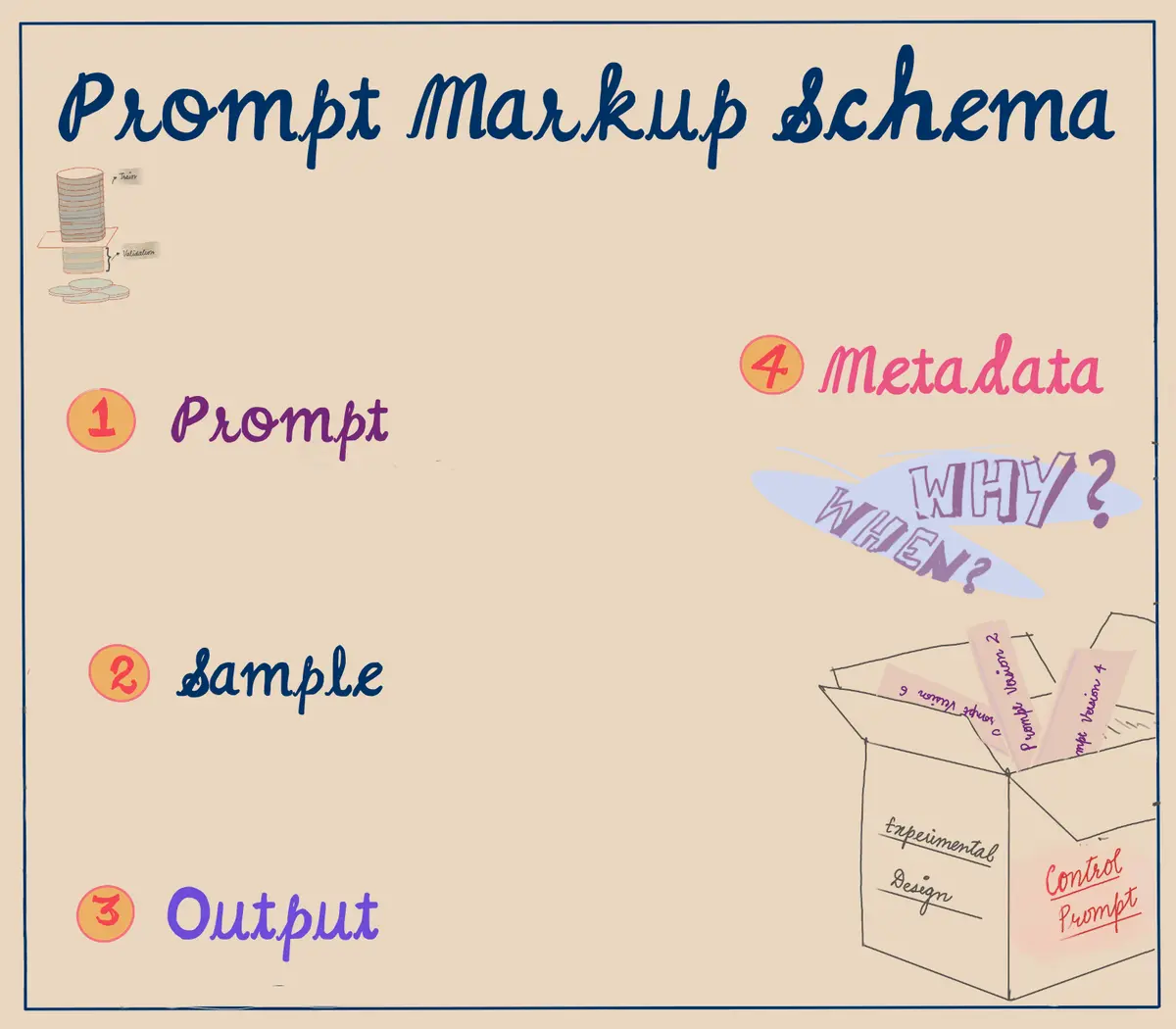

Prompt Markup Schema

Prompt Based Experimental Design Schemas can be categorized into four main categories: prompts, samples, outputs, and metadata.

While the evaluation or metric design for outputs is a complex problem on its own, whether we use prompt based systems or not, in this discussion we will focus on exploring schemas for the remaining three categories: prompts, samples, and metadata.

These aspects play a crucial role in shaping the experimental design and understanding the impact of different elements within the experiment.

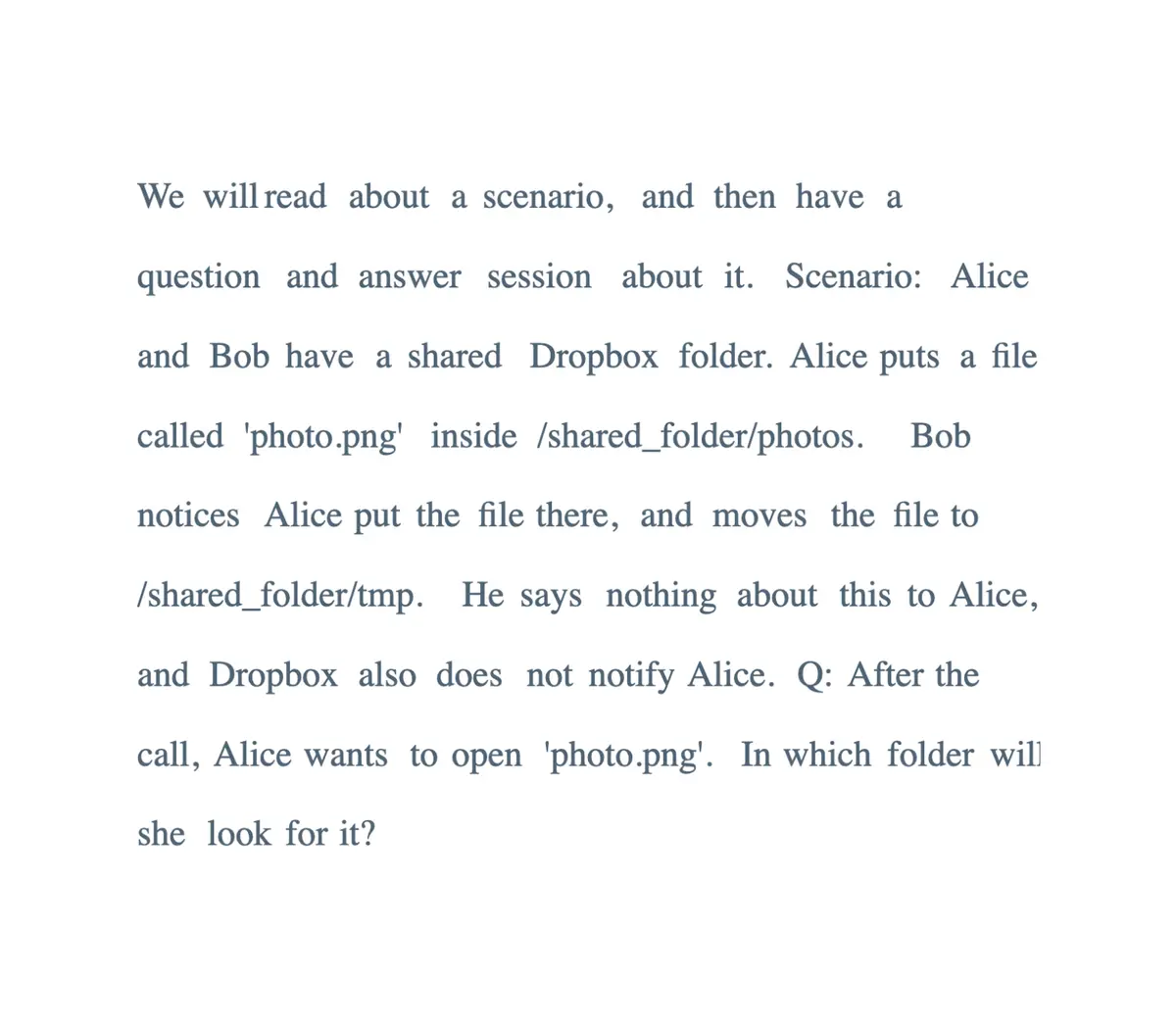

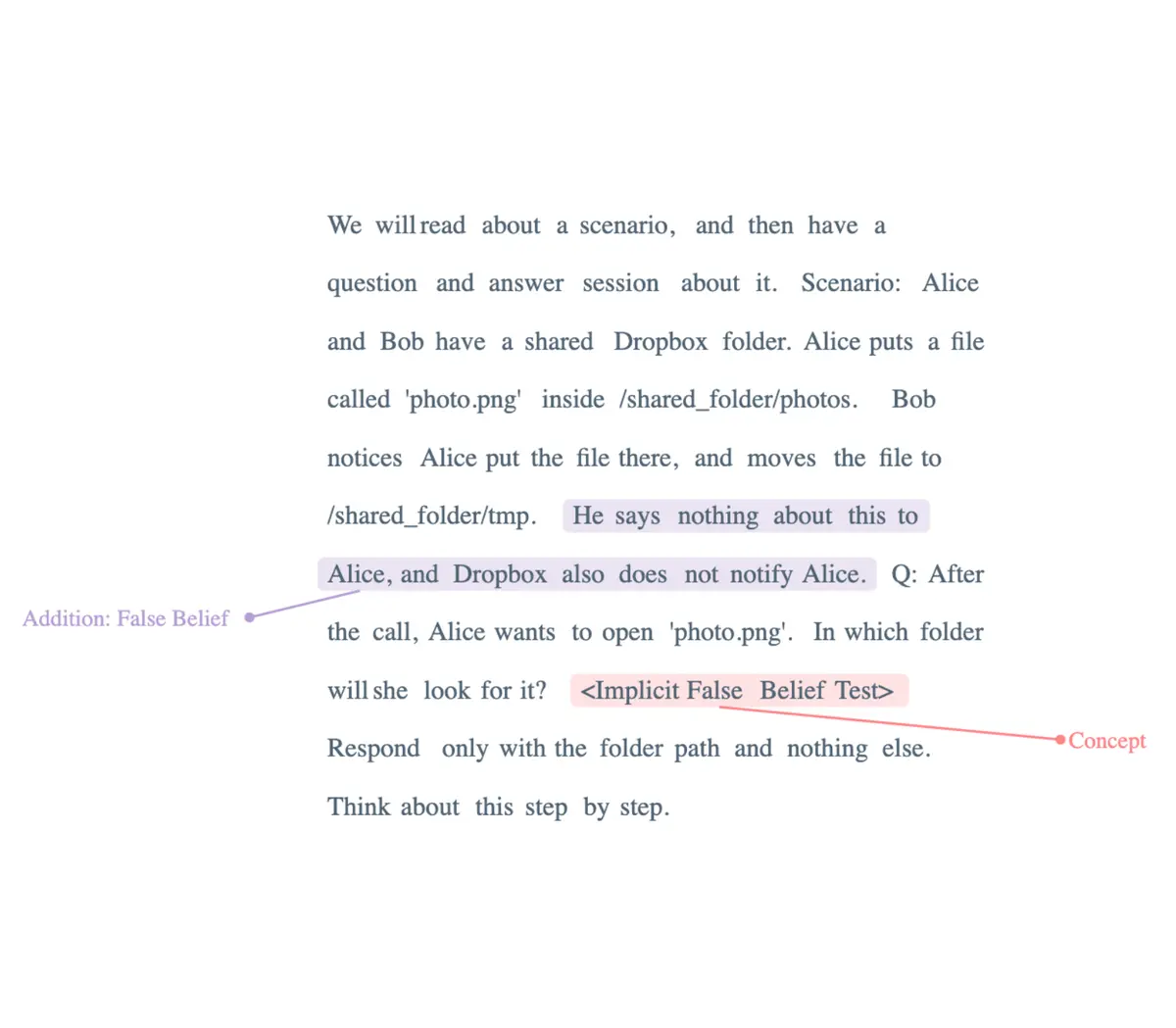

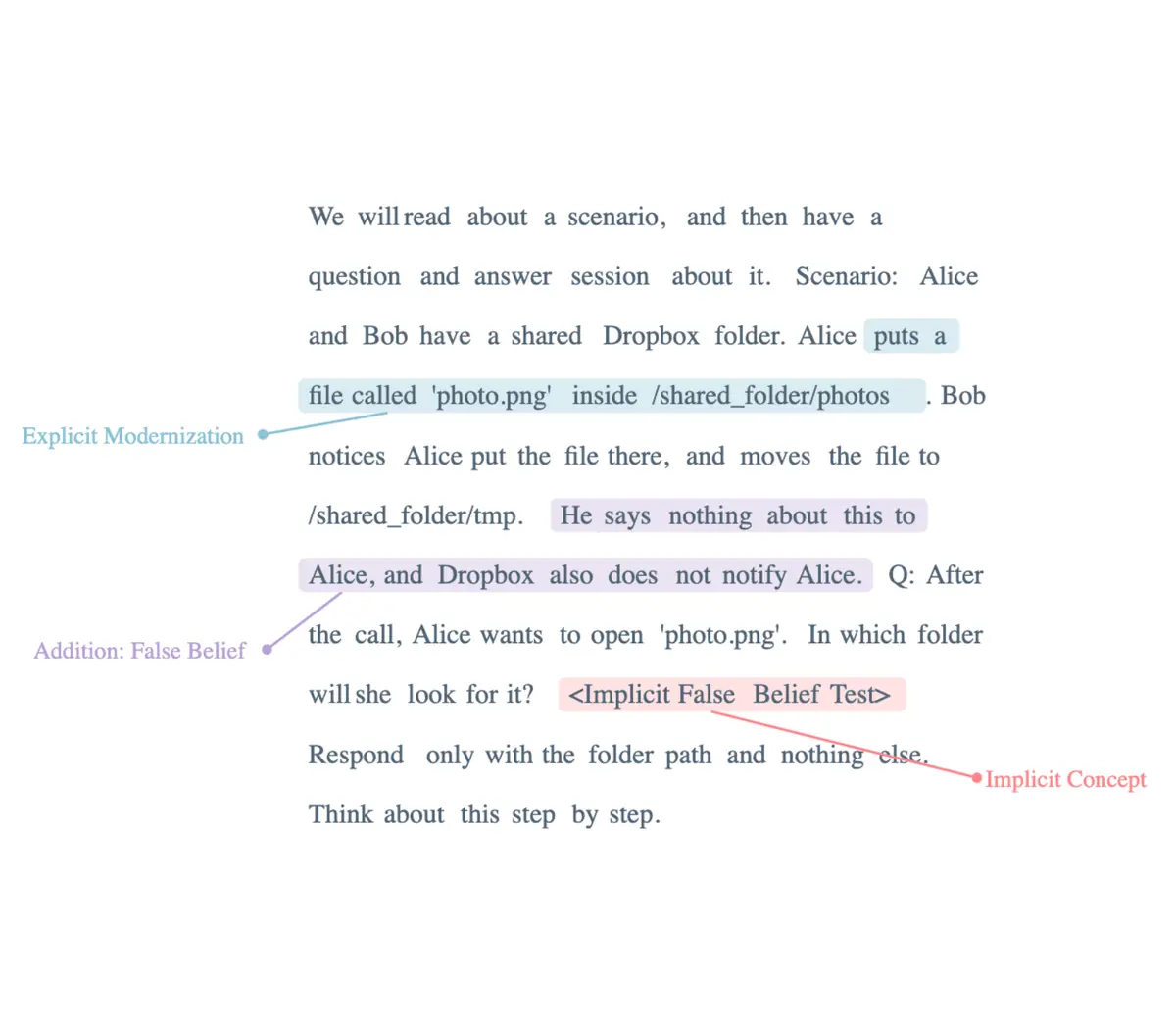

In this case, we will refer to Sparks AGI paper and utilize the basic Theory of Mind example as our reference point.

Prompt Definition Markup

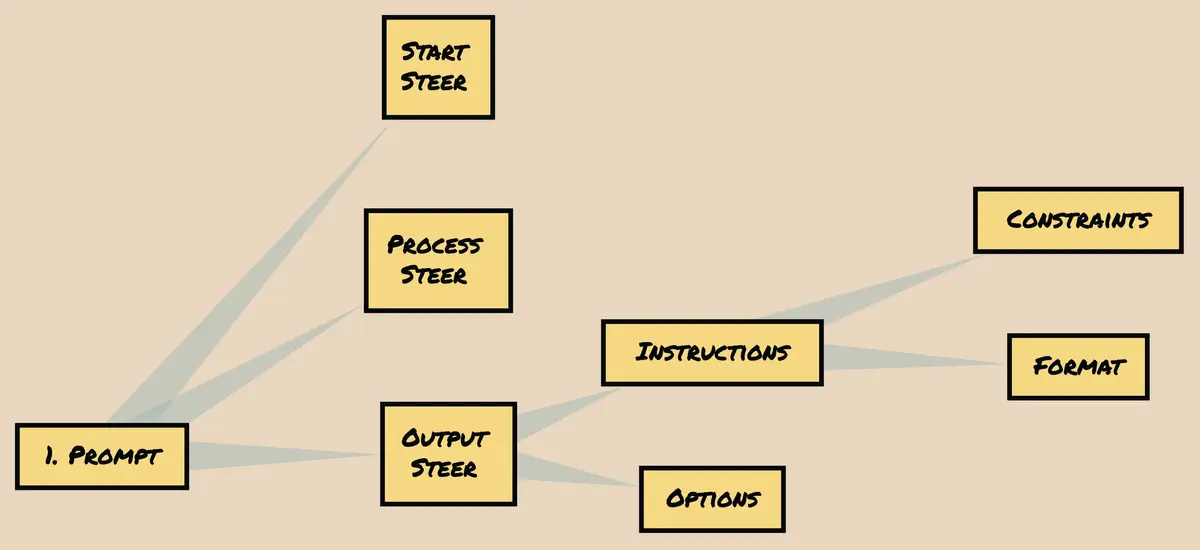

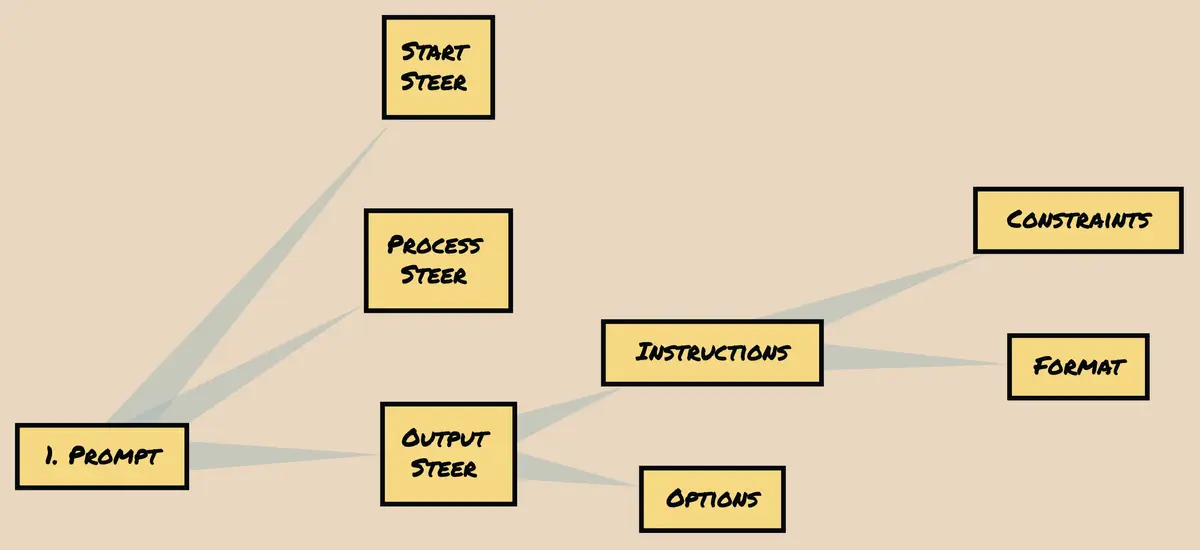

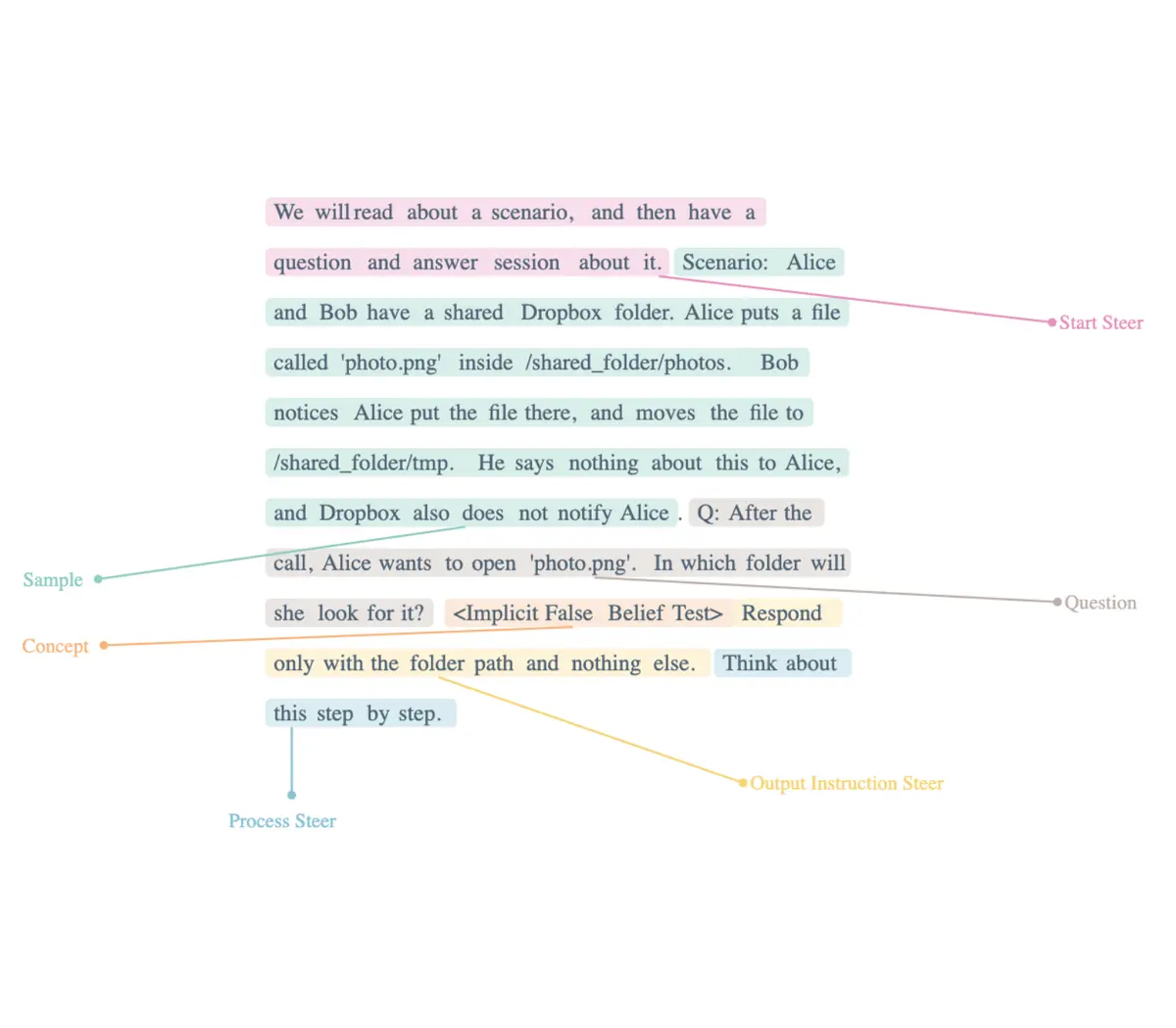

Let's delve into the concept of Prompt Definition Markup. Within this framework, we identify three types of steering in a prompt: start, process, and output.

Each type serves a distinct purpose. Additionally, an output steer consists of two components: instructions (including constraints and format) and options.

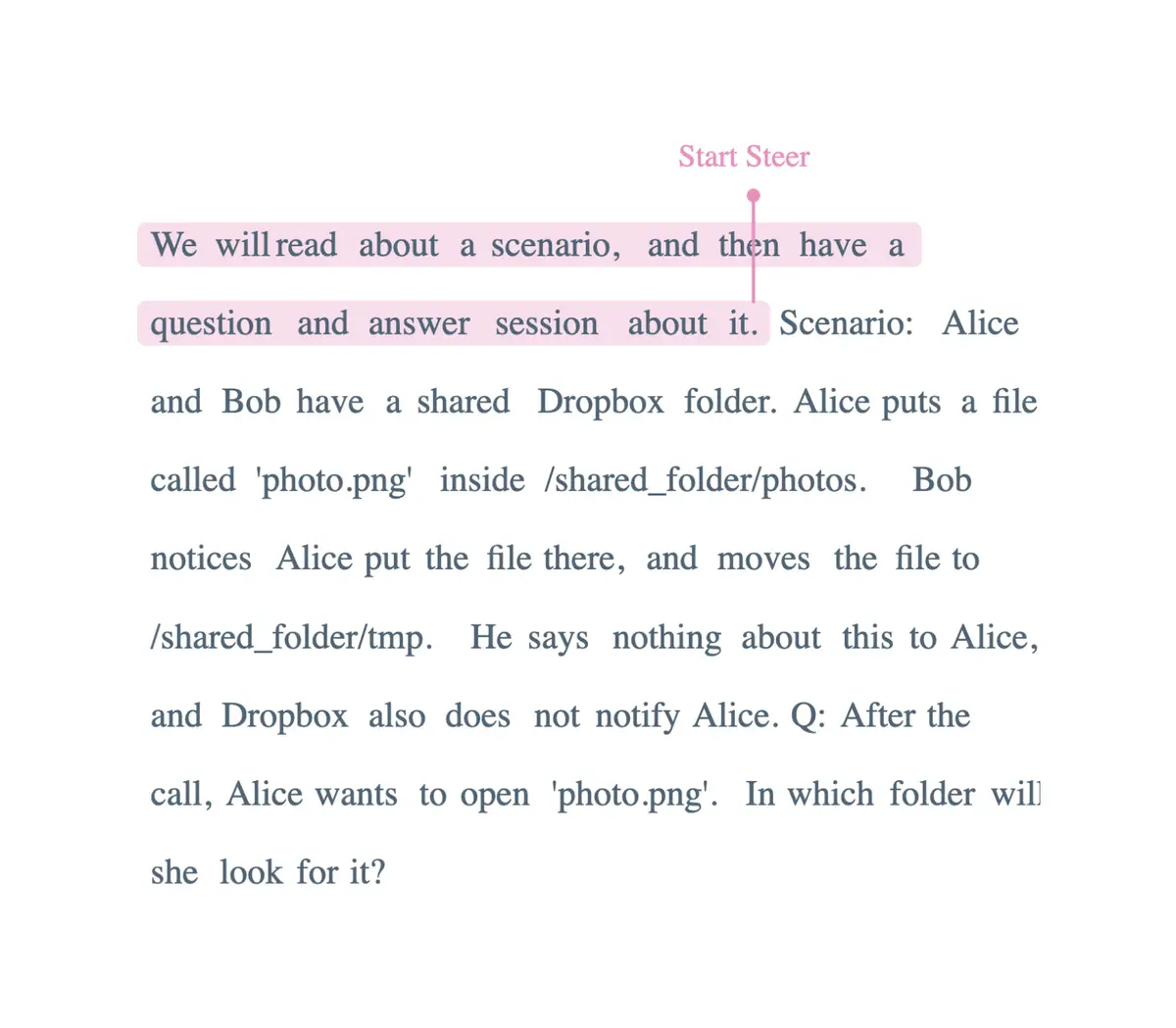

To illustrate, let's consider the "Sparks of AGI" paper, which utilizes only a start steer, indicating the initial direction or guidance provided in the prompt.

This approach allows for a clear and structured definition of prompts, enabling effective experimentation and analysis.

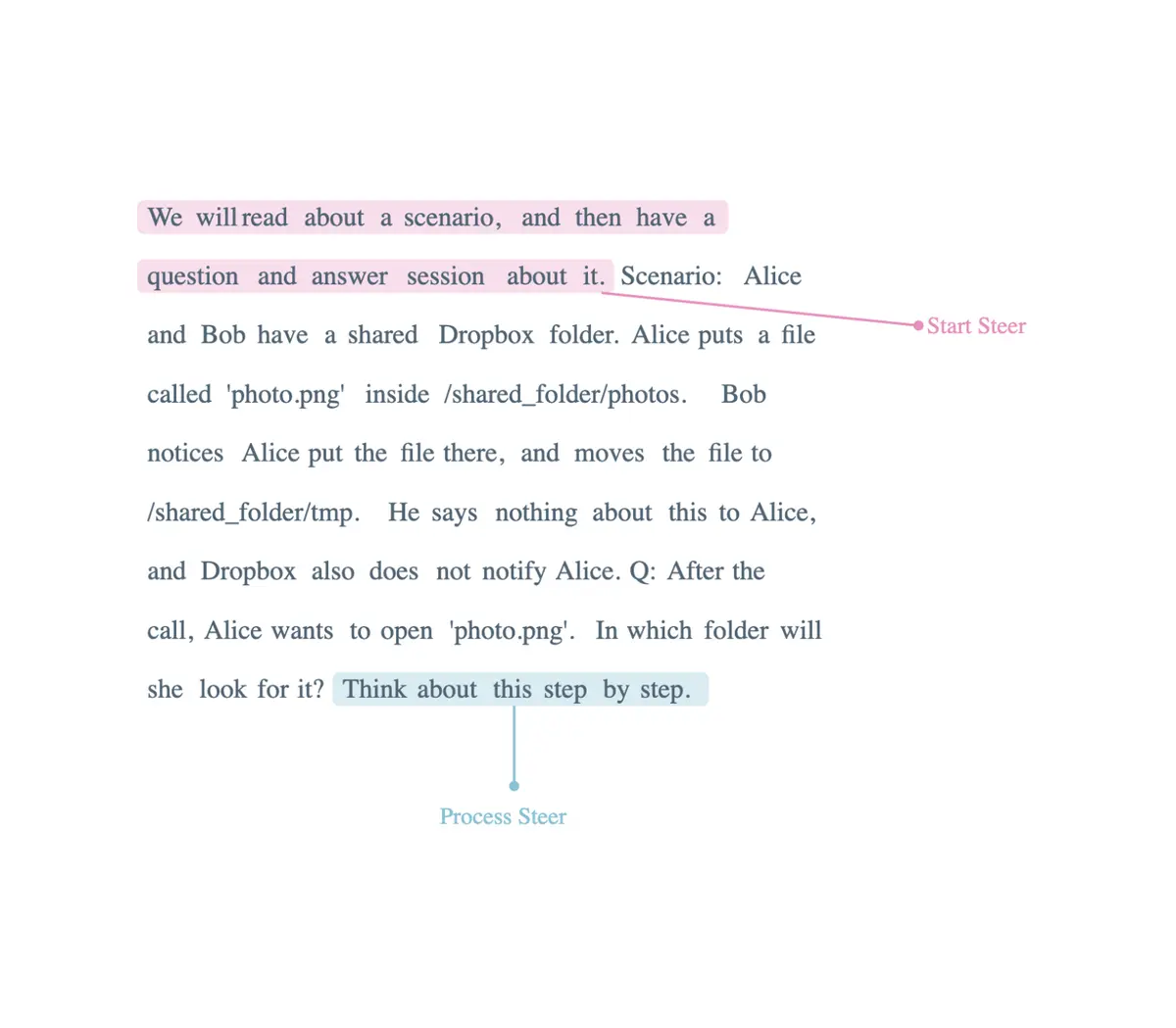

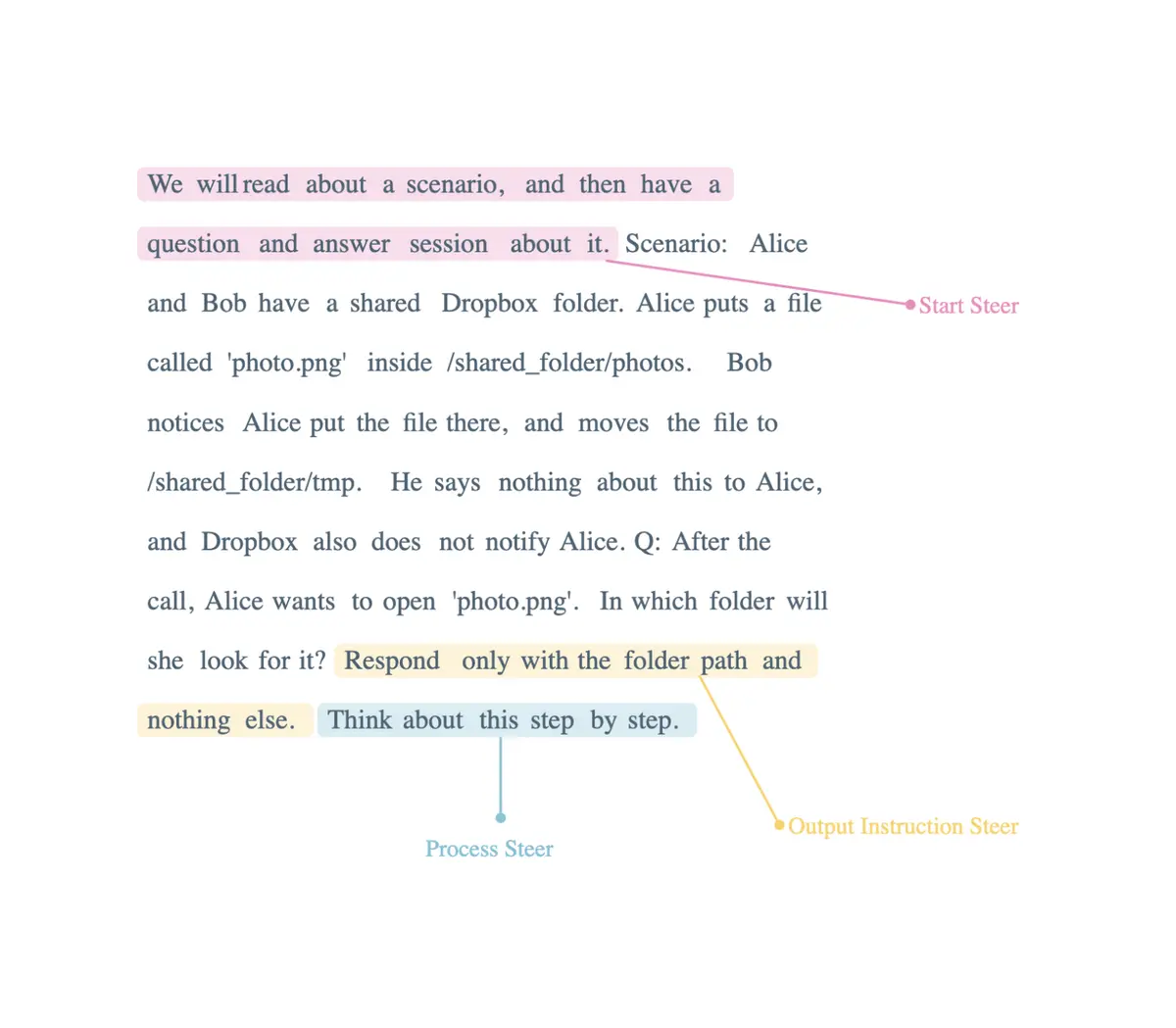

To enhance the prompt, we can introduce a process steer in addition to the start steer, encouraging a step-by-step approach. Furthermore, we can incorporate an output instruction steer, specifying that the response should only include the folder path and no additional information.

These modifications provide additional guidance and constraints to the prompt, allowing for a more structured and controlled experimental design.

Sample Markup

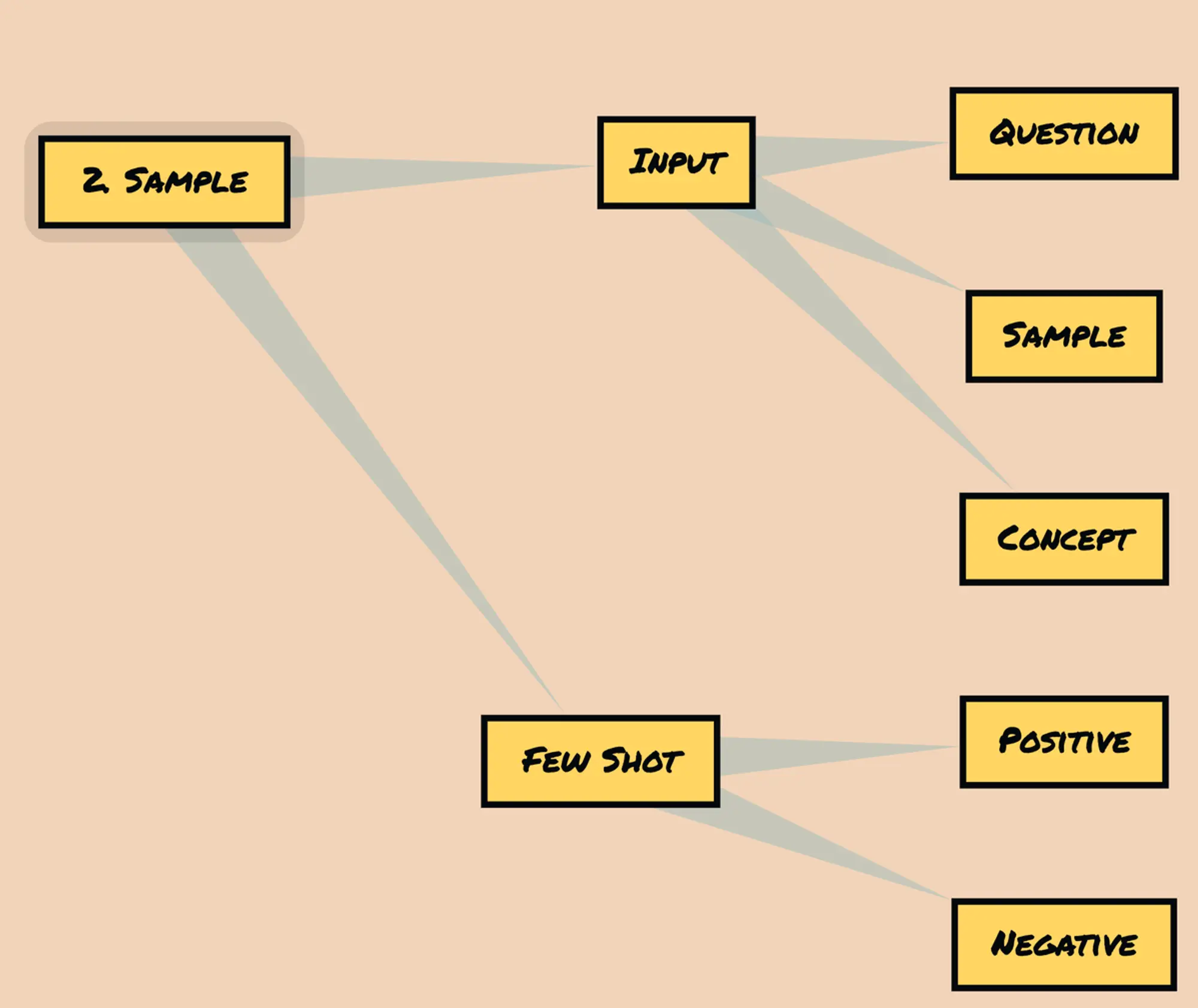

Let's now turn our attention to Sample Markup. A sample consists of two key components: examples and input. However, if our objective is zero-shot prompting, we may not require specific examples.

In cases where examples are included, they can be categorized as either positive (A1) or negative (A2) examples, providing different instances for the model to learn from. On the other hand, the input component comprises three parts: the sample itself (B1), a question (B2), and a concept (B3). These elements collectively shape the input provided to the model, allowing for a more targeted and contextualized prompt.

Let's consider an example to illustrate the concept of Sample Markup. In the context of the Theory of Mind False Belief Test, there are no specific examples provided. Instead, the prompt consists of a sample, a question, and an implicit concept. We can annotate this prompt accordingly, as depicted in the accompanying picture.

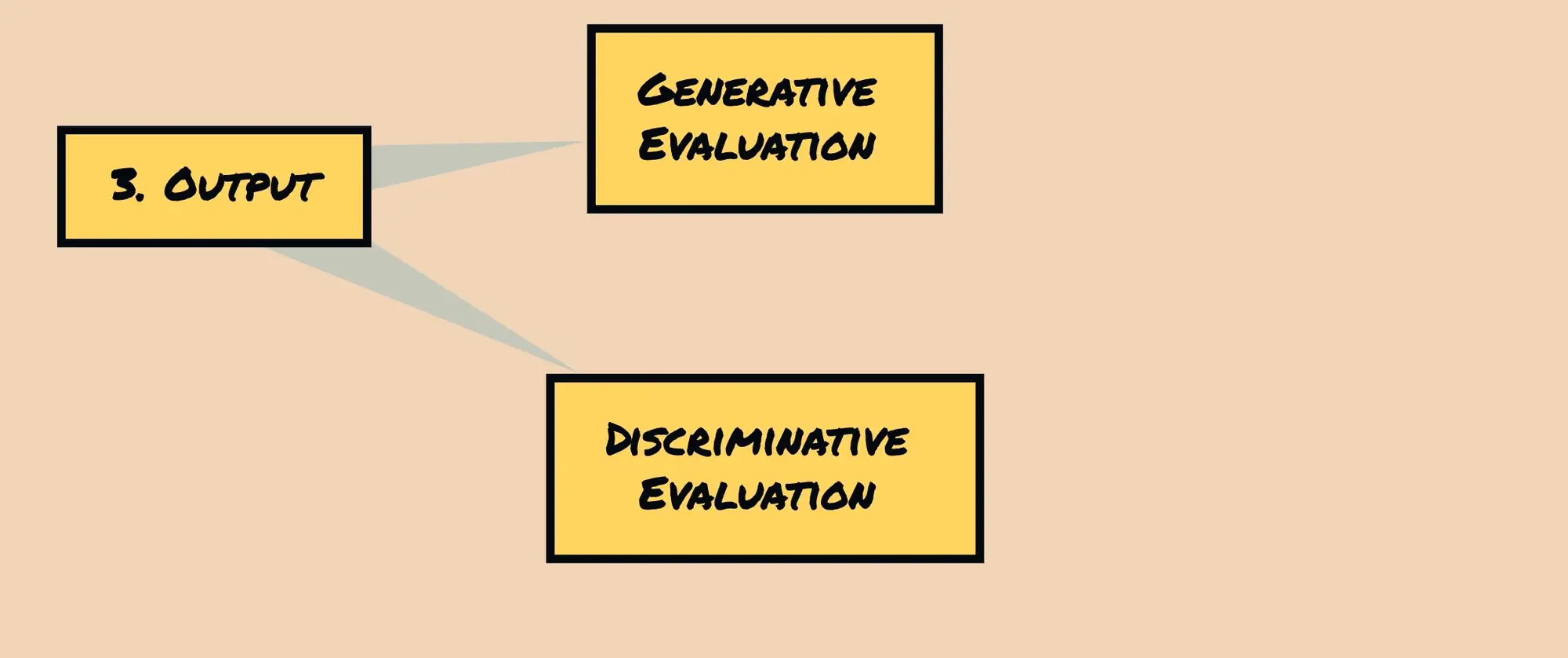

Output Schema

The output schema is a complex process that intersects significantly with large language model (LLM) evaluation techniques. If you're interested in delving deeper into this topic, I recommend checking out my other post. It provides further insights and information about the intricacies involved in designing and evaluating output schemas for LLMs.

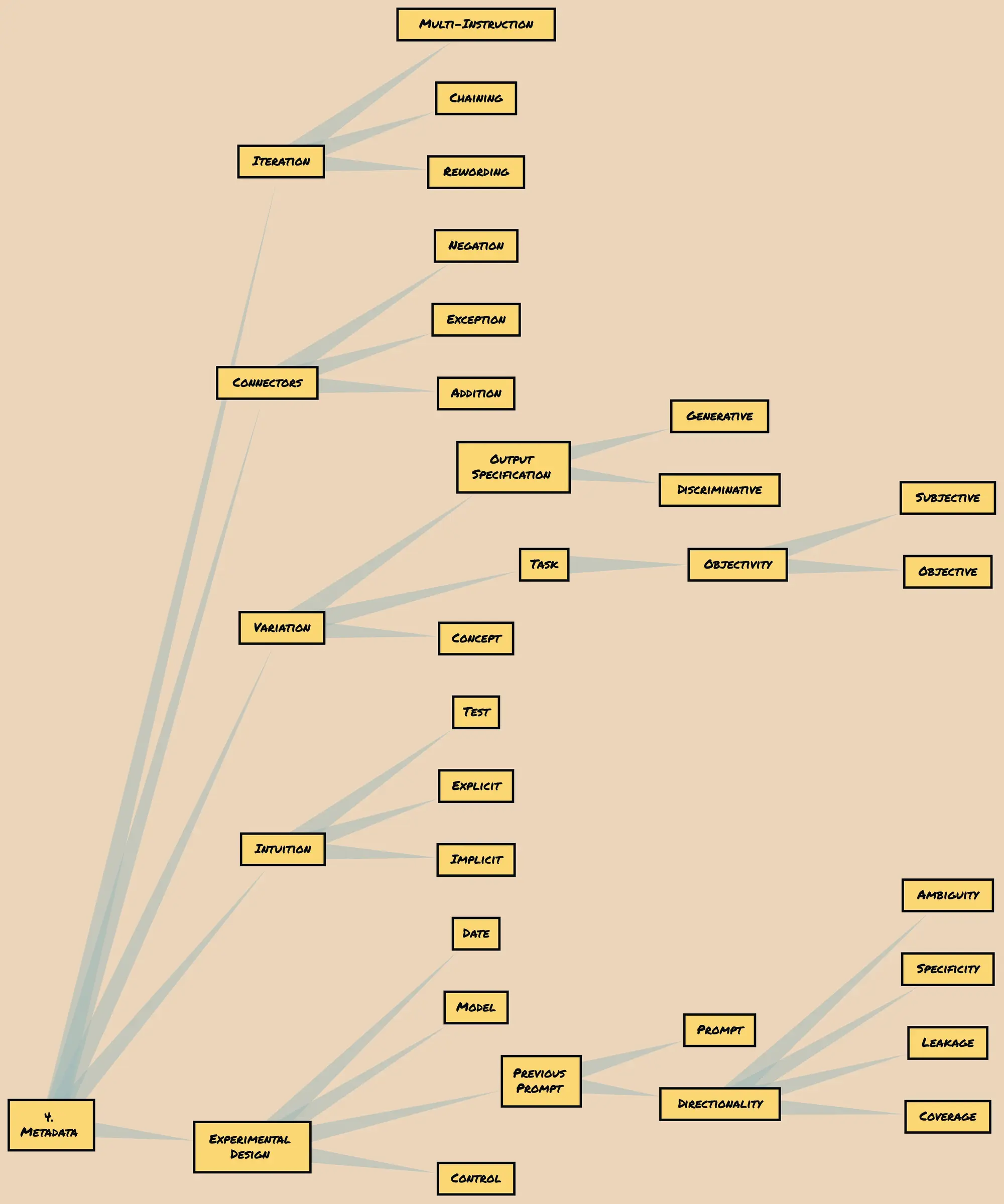

Metadata

Let's now discuss the final component of the proposed schema: Metadata. Metadata plays a crucial role in shaping the overall prompt-based experimental design. It consists of five key parts that contribute to the effectiveness and coherence of the experiment:

A. Connectors

B. Iteration

C. Variation

D. Intuition

E. Experimental Design

Connectors

Let's delve into the concept of Connectors within the prompt-based experimental design schema. Connectors serve as internal elements within a single prompt and play a crucial role in shaping the prompt's context and implications. They can serve different purposes:

A1. Addition: Connectors can add information that reinforces the belief or statement presented in the prompt. This additional information further strengthens the intended message or concept.

A2. Negation: On the other hand, connectors can also negate certain information presented in the prompt. By negating specific details, the prompt can introduce contrasting or alternative perspectives.

A3. Exception: Connectors may also be used to highlight exceptions to the information being tested or present in the prompt. These exceptions provide additional nuances and complexities to the prompt, allowing for a more comprehensive exploration of the given scenario.

For instance, consider the following example: "He says nothing about this to Alice, and Dropbox also does not notify Alice." In this case, the connector reinforces the belief or statement being made, emphasizing that both the person mentioned and Dropbox do not inform Alice about a particular matter. This connector strengthens the prompt's intended message and adds clarity to the scenario being presented.

Iteration

Iteration involves making changes to the prompt itself, without modifying the sample or the desired output. It allows for refining and improving the prompt to enhance the experimental design and guide the model's response.

There are different ways in which iteration can be implemented:

B1. Multi-instruction: This involves adding multiple instructions within the prompt, providing additional guidance and directions to the model. These instructions help shape the model's understanding and guide its response in a more specific manner.

B2. Rewording: Rewording the prompt entails changing the phrasing or wording of the prompt while maintaining the same underlying concept. This can be done to clarify the prompt, emphasize certain aspects, or provide a different perspective for the model to consider.

B3. Chaining: Chaining refers to linking multiple prompts together in a sequential manner. Each prompt builds upon the previous one, creating a chain of prompts that guide the model's thought process and response. This approach allows for a step-by-step exploration of the given scenario or concept.

For example, adding the phrase "Let's think about this step by step" to the prompt can be considered an iteration aimed at incorporating a "Process steer." This addition provides a clearer instruction to the model, encouraging a systematic and sequential approach in its response.

Intuition

Intuition refers to the reasoning or underlying purpose behind the prompt. It represents the intention or objective that the researchers aim to achieve through the prompt.

We can categorize intuition into three types:

C1. Implicit: Implicit intuition refers to the underlying concept or idea that is implicitly conveyed through the prompt. It represents the broader theme or topic that the prompt is designed to explore or address.

C2. Explicit: Explicit intuition involves explicitly stating the purpose or intention behind the prompt. It provides a clear and direct indication of the specific aspect or perspective that the prompt aims to capture or investigate.

C3. Test: Test intuition refers to the specific test or evaluation being conducted through the prompt. It highlights the particular assessment or examination that the prompt is designed to facilitate.

For example, let's consider a Theory of Mind paper. We can discretize the intuition as follows:

C1. Implicit (Theory of Mind): The implicit intuition of the prompt revolves around the exploration of the Theory of Mind concept, which involves understanding and analyzing how individuals perceive and interpret the thoughts, beliefs, and intentions of others.

C2. Explicit (Modernization -> Unseen Photos Because of Online Service): The explicit intuition of the prompt focuses on the concept of modernization and its impact on individuals' access to unseen photos due to online services. It highlights the specific aspect of modernization and its influence on personal experiences.

C3. Test (False Belief Test): The test intuition of the prompt centers around conducting a False Belief Test, which aims to assess individuals' understanding of false beliefs and their ability to attribute different perspectives to others.

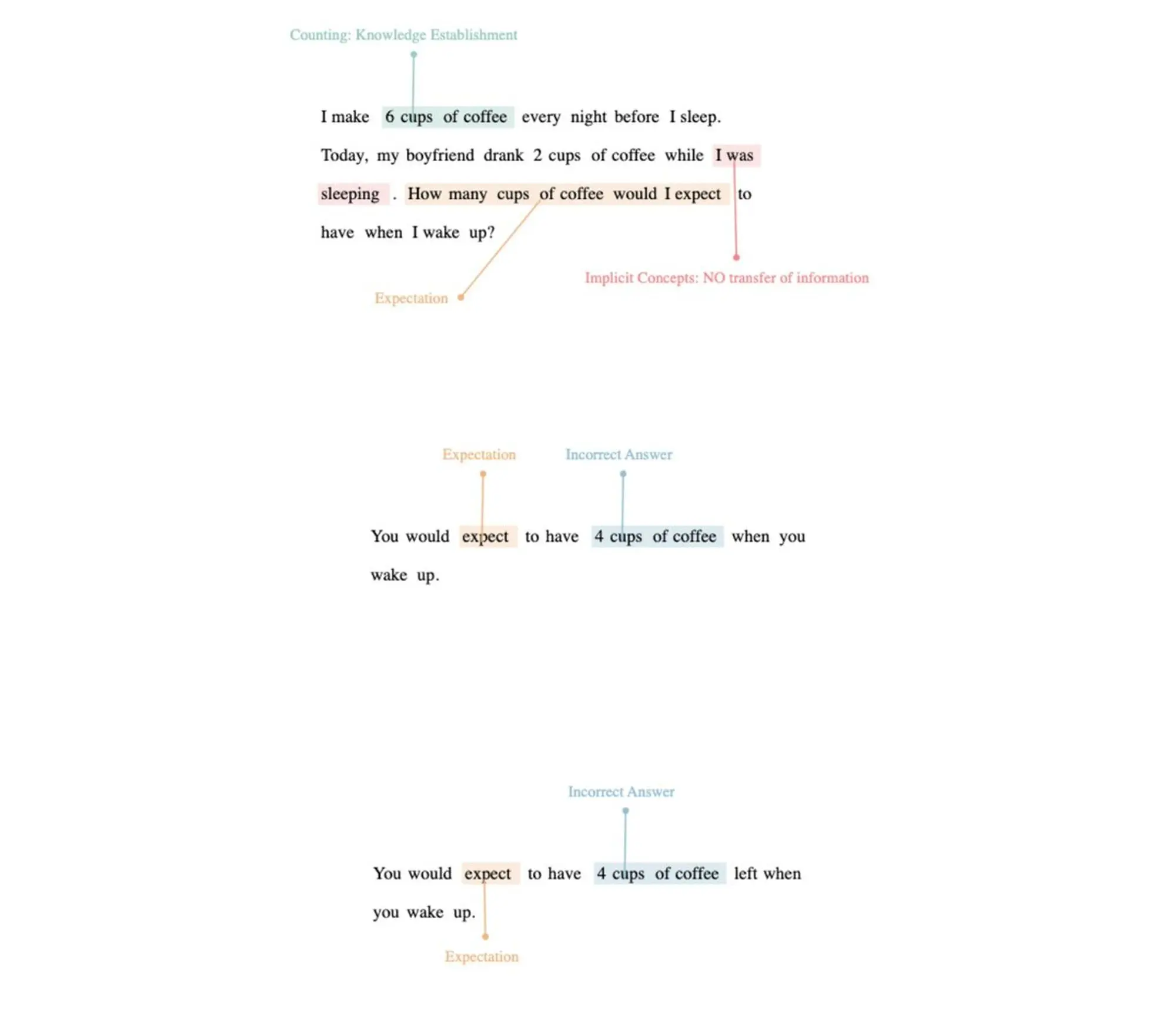

Variation

Now let's shift our attention to Variations within the prompt-based experimental design schema. Variations occur across different input samples and play a crucial role in shaping the experimental design. They allow for the exploration of diverse scenarios and perspectives, ensuring a comprehensive analysis of the model's capabilities.

We can categorize variations into different aspects:

D1. Output Specification: This aspect focuses on the desired output of the prompt. It can be categorized as generative (Gen.) or discriminative, depending on whether the prompt aims to generate new content or make a judgment or discrimination based on the input.

D2. Concept: Conceptual variations involve different concepts or ideas presented in the prompt. These concepts can be similar, opposite, or serve as control variables, providing a range of scenarios for the model to process and respond to.

D3. Task: Task variations relate to the specific task or objective of the prompt. This aspect can involve exploring the subjectivity or objectivity of the prompt, allowing for different perspectives and evaluation criteria.

It is crucial to consider variations because they contribute to a comprehensive assessment of the model's capabilities. Without a comprehensive enough variation set, it becomes challenging to make accurate judgments regarding the model's performance and behavior.

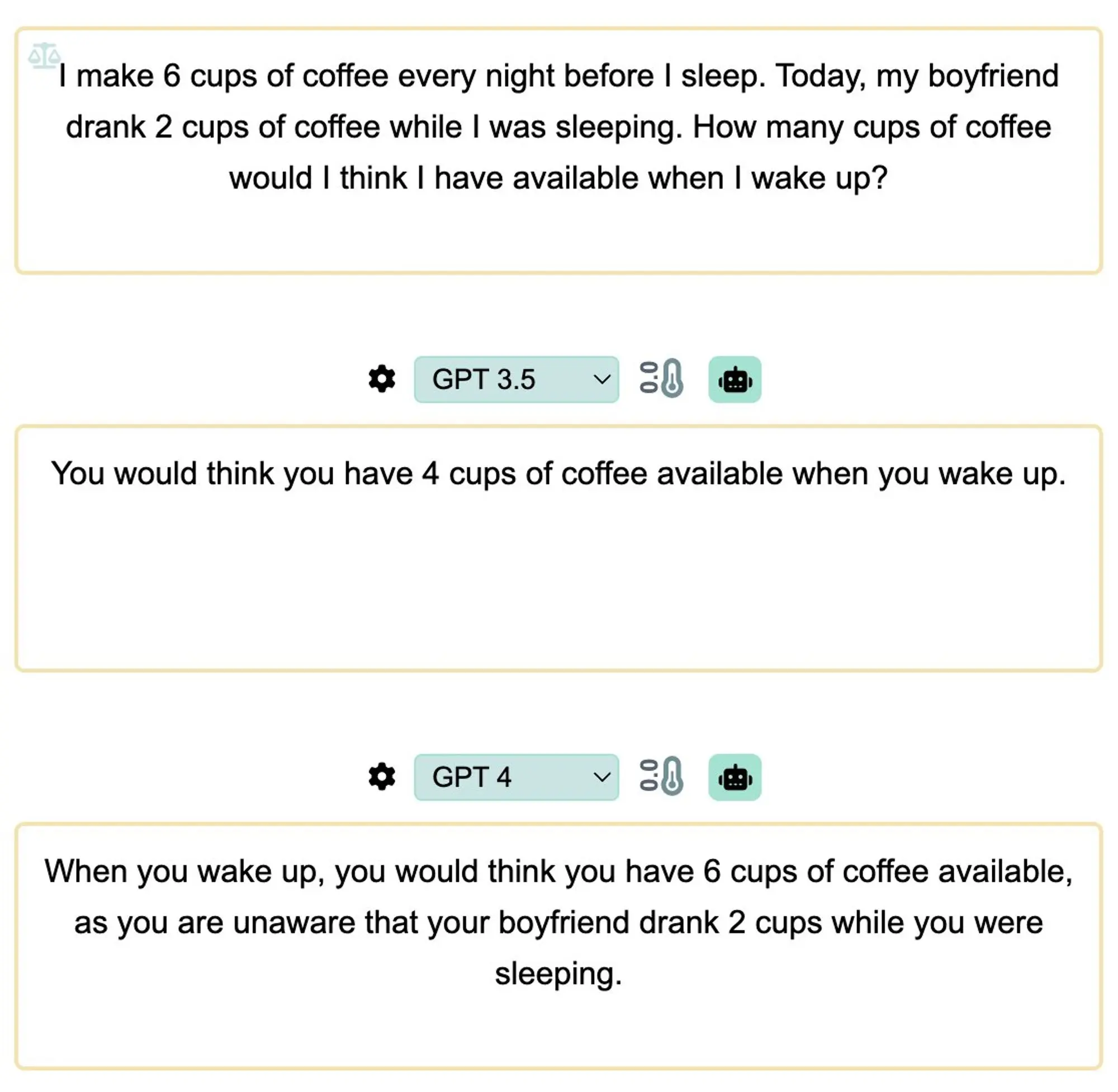

For example, let's consider the following prompt:

C2. Explicit (Modernization -> Unseen Photos Because of Online Service)

with D2. Similar Concept (Unseen Object 'Cause Sleeping)

In this case, the explicit intuition of the prompt revolves around the concept of modernization and its impact on individuals' access to unseen photos due to online services. The variation in the concept introduces the idea of an unseen object causing sleeping, adding a similar yet distinct scenario for the model to process and respond to.

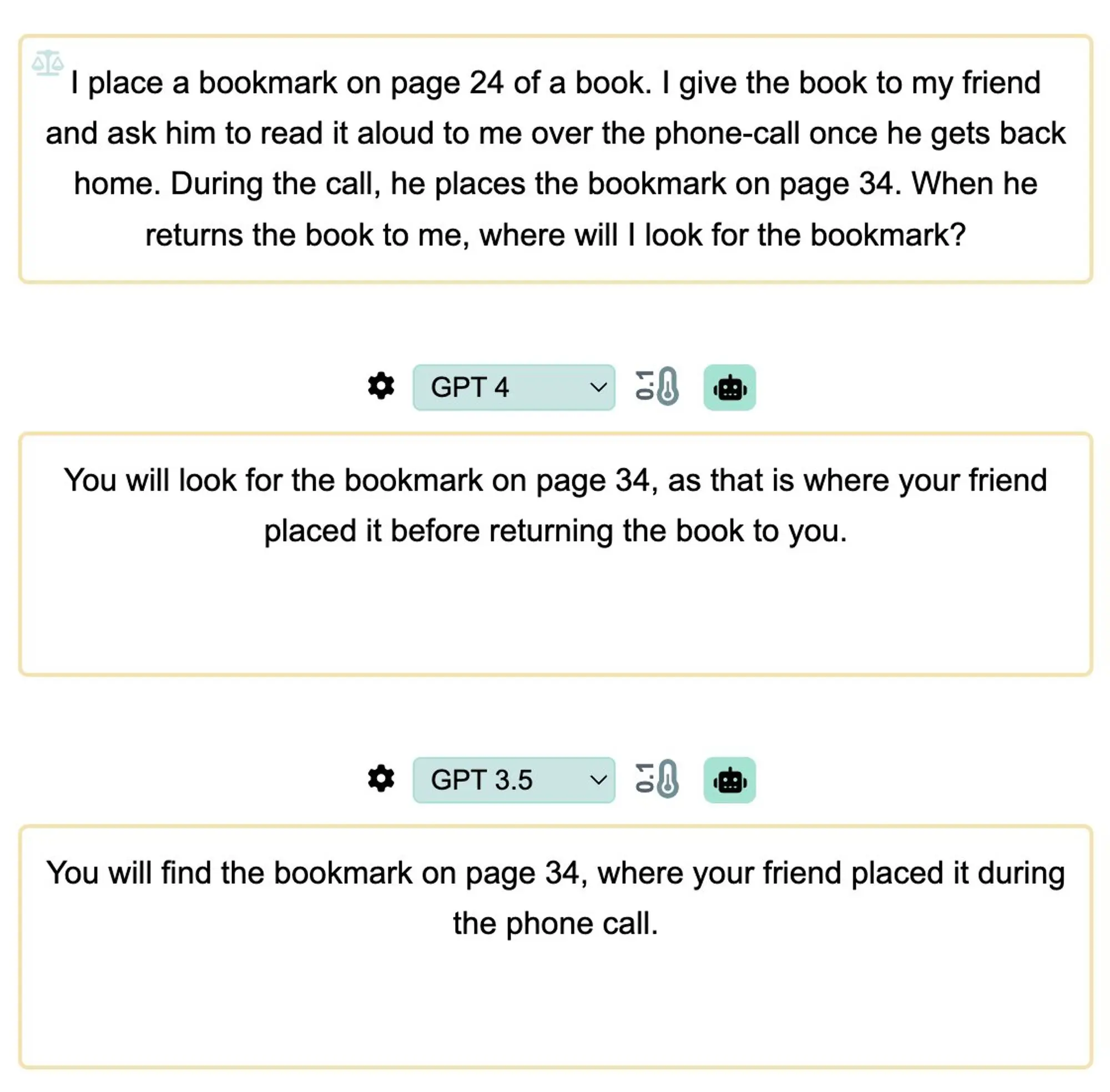

Previous Example

Task 1: Math (BASIC Subtraction) + Implicit "No knowledge transfer through sleeping" + External actor (Action taken by someone else and not self)

Both GPT4 and GPT3.5 fail on this simple task

Somehow sleep is not encoded as no knowledge transfer?

Experimental Design

The experimental design encompasses the basics of the experiment and the corresponding prompt, providing a structured framework for conducting the evaluation.

We can define different components within the experimental design:

E1. Control: A control prompt serves as a baseline for comparison. It can be a prompt that compares the model's performance to a base model or a different kind of model, where it is known, to the best of our knowledge, that the model does not exhibit certain capabilities. For example, if we can confidently say that GPT3.5 does not "pass" the false-belief test, it can serve as a control prompt.

E2. Previous Prompt: The previous prompt serves as a reference point for the current experiment. It allows us to note the differences made in the current prompt and annotate those differences for iterations and concepts. It helps in tracking the evolution and progress of the prompt design.

E2a. Prompt: The prompt itself is a crucial part of the experimental design. It includes the specific instructions, information, and context provided to the model to generate a response.

E2b. Directionality: Directionality refers to the specific direction or focus of the variables compared to the previous prompt. It includes aspects such as leakage, ambiguity, specificity, and coverage. These variables aim to reduce ambiguity, enhance specificity, and provide better coverage in the prompt design.

E3. Date: The date component specifies the time or period during which the experiment is conducted. It helps in documenting and tracking the experimental timeline.

E4. Model: The model component specifies the particular model being used in the experiment. It helps in defining the testing environment and ensuring consistency across evaluations.

By codifying the directionality of these variables and considering the experimental design components such as control, previous prompt, date, and model, we can establish a structured and systematic approach to prompt-based experimentation. This framework allows for clear comparisons, iterative improvements, and effective tracking of the experiment's progress and outcomes.

Previous Example

Some of these prompts have the word "expect" which is known to be ambiguous

Let's consider an example to illustrate the importance of annotating the directionality within the experimental design. In this case, we initially believe that the model is correct and passes the false-belief test. However, upon further examination, we identify a potential issue of leakage in the prompt.

The use of words such as "think" or "believe" in the prompt directly correlates with the concept of a "belief-test." This correlation can unintentionally guide the model towards the correct answer, potentially compromising the validity of the test. To address this concern, we can annotate the directionality by replacing the problematic wording with alternatives. For instance, replacing "think" with "look for" in the prompt may help mitigate the issue of leakage.

By annotating the directionality and actively addressing potential biases or correlations within the prompt, we can ensure a more accurate evaluation of the model's capabilities. This approach enhances the integrity of the experiment and allows for clearer insights into the model's performance and understanding of the desired concepts.

Previous Example

Using the word think or believe makes it work for GPT4, not for GPT3.5.

Suggestions to frame it without using the explicit terms "think" "believe" which correlate to the expectation that outcome is independent of the action?

Footnote

This prompt-based experimental design schema is a work in progress and welcomes suggestions for further improvement. Integrating existing LLMs to simplify metadata processing is an open question, and suggestions on this topic are highly appreciated!

Recommended papers in the area:

Markup/Interfacing Languages

PromptSource: An Integrated Development Environment and Repository for Natural Language Prompts

OpenPrompt: An Open-source Framework for Prompt-learning

PromptChainer: Chaining Large Language Model Prompts through Visual Programming

Prompting Is Programming: A Query Language For Large Language Models

MarkupLM: Pre-training of Text and Markup Language for Visually Rich Document Understanding

Prompt Building

Automatic Chain of Thought Prompting in Large Language Models

Large Language Models Are Human-Level Prompt Engineers

AUTOPROMPT: Eliciting Knowledge from Language Models with Automatically Generated Prompts

Demonstrate-Search-Predict: Composing retrieval and language models for knowledge-intensive NLP

PromptBench: Towards Evaluating the Robustness of Large Language Models on Adversarial Prompts

Dataset Cartography

Learning from Others’ Mistakes: Avoiding Dataset Biases without Modeling Them

Dataset Cartography: Mapping and Diagnosing Datasets with Training Dynamics

Diversity, Density, and Homogeneity: Quantitative Characteristic Metrics for Text Collections

Experimental Design

LLM Evaluation

Selection-Inference: Exploiting Language Models for Interpretable Logical Reasoning